Literary Devices - Tumblr Posts

@discjude Thank you! I'm glad it could turn out to be helpful to you! If you keep track, I'd love to know how many you manage to use—that's a cool idea.

I'm thrilled the Japeth one got to you! (When I came up with his list, I specifically thought: "I wonder if Jude would have anything to say about it?")

Kei is kind of a hard one, to me. Off the top of my head, I'd assign him: turning point, in medias res, and third person limited pov, which is just another way of saying he's a little unknowable, and/or I don't know him well enough as a character aside from the role he played in forwarding the plot. And, I'm referencing his sudden appearance and relevance.

⸻

I should have assigned symbolism to someone, so that goes to Sophie, Guinevere, and the Storian.

Arthur (and the kingdom of Camelot itself) get magical realism/fabulism, and haunting the narrative. And a less modern way of defining Lancelot could've been "the vernacular." Also, Merlin gets puns.

And, I came up with overlap for Rhian I and Rhian II: oxymoron, paradox, and passive voice (especially when used to displace blame onto another, or to leave out a designated, clear subject performing the deed).

⸻

Latin is a roundabout way of saying: “Rafal is old.”

(In One True King, I'm pretty sure Sophie freaks out and derides him, calling him "Father Evil.")

The more elaborate explanation is that he does not and will never suffer from "belatedness." (Except, in the context of Soman drawing inspiration from elsewhere.)

Rafal is the “first,” in a sense, which lends to him the special, rare advantage of not feeling self-conscious of his work. He was likely the "innovator" of Evil, to an extent, we could speculate, and I doubt he was predated by too many exceptional villains, especially considering how he's held up by those at The Black Rabbit as some kind of exemplar, the Master of Evil, who gets a free pass in on some basis of his actual prodigiousness, something other than his just being a feared authority figure.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but: every other villain or antagonist, major or minor, in the entire series (not counting the Storian) exists after him in time, or exists because of him and the influence he exerts, the hostility he elicits, the violence he incites. He's the proverbial "giant," and others stand on his shoulders.

Here, I briefly trawled the internet:

"Quick Reference. In Harold Bloom's theory of literary history (see anxiety of influence), the predicament of the poet who feels that previous poets have already said all that there is to say, leaving no room for new creativity. From: belatedness in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms » Subjects: Literature."

"Belatedness definition: The state or quality of being belated or of being too late."

In addition, while Latin is mostly a reference to Rafal’s age and his lack of suffering from belatedness, it's also the provenance of lots of words from the English language. (I know the Greeks as epic poets came first, but Latin works better for these comparative purposes.) That's why I tied the concept of the etymological roots of words into his list.

If Rafal were a modern scholar, I'm tempted to say he'd pursue the study of philology because it works well for him, as a symbol:

"A theory of language development which traces the ‘family tree’ of modern natural languages like English, French, and German back to their historical origins. The central point of interest of such research is to show the common ancestry of words dispersed across several languages."

Or the common ancestry of all Evil. Horrible, isn't it?

Plus, we might have a sliver of evidence for this so-called "great inheritance" in Fall. Whatever he said to the demimagus in its language or in the language of sorcery (or if we take into account the spells and incantations of SGE in general) they all seem to be derived from Latin, as is common practice among authors.

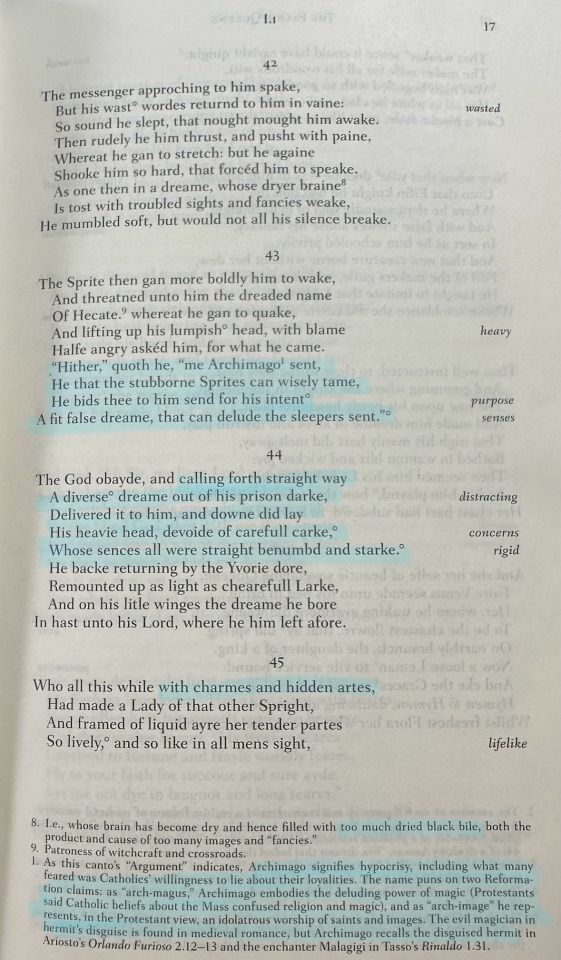

Thus, he's old—despite being part of an archetype greater than himself anyway. Because, actually, sorry to break it to you: he’s an “Archimago” figure!

(Well, by my interpretation, at least. And besides that, other literary characters I don't know probably predate Edmund Spenser's Archimago as well.)

Thusly, we have:

Lecherous, Bad "Catholic" Rafal -> Making Good Holy Knights Doubt Their True Love, Truth, and Faith & Posing As An Ancient Hermit Since 1590.

I promise I'm not insane. If anyone would like some reference:

SGE Characters as Literary Things

(Not all of these are actual literary or rhetorical devices; some are just writing techniques, forms, genres, mediums, etc.)

This is a bit abstract, so I’m curious about how subjective these might be. Does anyone agree or disagree? And feel free to make additions if you think I left anything out, or request another character that isn’t here.

Hopefully this makes (intuitive?) sense. As always, I'm willing to explain my thought process behind any of the things I've listed.

Also, anyone can treat this like a “Tag Yourself” meme, if you want. Whose list do you most relate to, use, or encounter?

⸻

LANCELOT (I know—how odd that I’m starting with a minor character and not Rafal, but wait. There’s a method to my madness. Also, watch out for overlap!):

Metonymy, synecdoche (no, literally, to me, these are him.)

Zeugma

Analogy

Figures of speech

Slang, argot

Colloquialisms

Idioms

TEDROS:

Simile

Metaphor

Rhyming couplets

Rhyme schemes

Sonnets

Commercial fiction

Coming-of-age genre

Line enjambment

Overuse of commas

Cadence, prose speech

Waxing poetic, verse (not prose)

Alliteration

Kinesthetic imagery

Phallic imagery/sword sexual innuendos (sorry)

The chivalric romance genre

AGATHA:

Anaphora, repetition

Semicolon, periods

Line breaks

Terse, dry prose

Semantics (not syntax)

Elegy

Resonance

Consonance, alliteration

Pseudonym

Narrative parallels

Realism

Satire

SOPHIE:

Sophistry (yes, there is a word for it!)

Imagery

Italics, emphasis

Em dash

Aphrodisiac imagery

Unreliable narrator, bias

Rashomon effect

Syntax (not semantics)

Diction

Chiasmus (think: “Fair is foul and foul is fair.”)

Rhetorical purpose

Provocation, calls to action

Voice, writing style

Rhetorical modes: pathos, logos, ethos

Metaphor

Hyperbole, exaggeration

Sensationalism, journalism

Surrealism

Verisimilitude

Egocentrism

Callbacks (but not foreshadowing or call-forwards)

Narrative parallels

Paralepsis, occultatio, apophasis, denial

Hypothetical dialogue

Monologue

JAPETH:

Sibilance

Lacuna

Villanelle (an obsessive, repetitive form of poetry)

Soliloquy

ARIC:

Sentence fragments

RHIAN (TCY):

Unreliable narrator

Setup, payoff

Chekhov’s gun

Epistolary novel

RHIAN (prequels):

Multiple povs

Perspective

Dramatic irony

Situational irony

Chiaroscuro (in imagery)

Endpapers

Frontispiece

Deckled edges

Narrative parallels

Foreshadowing

Call-forwards

Foil

Death of the author

RAFAL:

Omniscient narrator

Perspective

Surrealism

Etymology

Word families or 'linguistic ecosystems'

Latin

Verbal irony

Gallows humor

Narrative parallels

Call-forwards

Circular endings

Parallel sentences or balanced sentence structure

Narrative parallels

Foil

Juxtaposition

Authorial intent (“return of the author”)

HESTER:

Protagonist

Allusions

Gothic imagery

ANADIL:

Defamiliarization

Deuteragonist (second most important character in relation to the protagonist)

Psychic distance

Sterile prose

Forewords, prologues

Works cited pages

DOT:

Tone

Gustatory imagery

Tritagonist (third most important character in relation to the protagonist)

KIKO:

Sidekick

Falling action

Dedications, author's notes, epigraph, acknowledgements

Epitaph (Tristan)

BEATRIX:

Pacing

Rising Action

Climax

HORT:

Unrequited love

Falling resolution

Anticlimax

Malapropism

Innuendo

Asides

Brackets, parentheses

Cliché

EVELYN SADER:

Synesthetic imagery

Villanelle

Foreshadowing

AUGUST SADER:

Stream of consciousness style

Imagery

Foreshadowing

Coming-of-age genre

Elegy

Omniscience

Rhetorical questions

Time skips, non-linear narratives

Epilogues

MARIALENA:

Diabolus ex machina

Malapropism

Malaphors, mixed metaphors

Slant rhyme

Caveat

Parentheses

Footnotes

MERLIN:

Deus ex machina

Iambic pentameter

Filler words

BETTINA:

Screenwriting

Shock value

@discjude Yes! I'm so glad you agree with the Rafal-Latin interpretation. In my mind, Evil follows him around like a toxic contagion, like a contaminant, visible fog that everyone breathes and goes insane over. Meanwhile, Rhian's Evil is more insidious. I don't think it would be airborne in that same sense. Rhian's Evil, while dormant, would probably just mark him as a "carrier" of the symbolic disease. And, of course, Rafal (or Rhian) poisoned the entire bloodline.

Also, the Latin-relevance-to-modern-English thought sort of made me think: what if it were forcibly relevant, like at times when it wouldn't occur "naturally"? That could relate to the spirit of Rafal being beaten alive again and again and it never becoming irrelevant to the plot at any point, like you said, ingrained in everything. At some point, after the plot's undergone various cycles of the same after the same, it could probably seem like it's beating a dead horse.

And yet, Rafal himself would probably demand to be brought up again and again anyway, given his ego, so the plot thread never dies since it's not allowed to, in a kind of willful, conscious way possibly? Because, of course, he always has to be relevant. I can just picture him thinking, stubbornly deciding: fine, if I must be dead, I'll do it my way, on my terms, and still remain in the shadows, puppeteering everyone from beyond the grave. End of story, except it's not. The story is still mine. It always was. No matter how far the story gets from me, there's no getting rid of me.

⸻

If you're interested, here's a second Rafal connection. Disclaimer: I barely know anything about this since I just heard about it the other week and most of my sources are Wikipedia:

There is a particular school of thought in literary theory called the "hermeneutics of suspicion," which is actually just a way of saying appearances belie reality, as usual.

hermeneutic (adj.) = "Of, relating to, or concerning interpretation or theories of interpretation."

"The hermeneutics of suspicion is a style of literary interpretation in which texts are read with skepticism in order to expose their purported repressed or hidden meanings. [...]"

"[...] a similar view of consciousness as false. [...] This school is defined by a belief that the straightforward appearances of texts are deceptive or self-deceptive and that explicit content hides deeper meanings or implications."

"According to literary theorist Rita Felski, hermeneutics of suspicion is 'a distinctively modern style of interpretation that circumvents obvious or self-evident meanings in order to draw out less visible and less flattering truths.'"

"Felski also notes that the 'hermeneutics of suspicion' is the name usually bestowed on [a] technique of reading texts against the grain and between the lines, of cataloging their omissions and laying bare their contradictions, of rubbing in what they fail to know and cannot represent."

In contrast, we have:

"[...] a hermeneutics of faith, which aims to restore meaning to a text, [...]"

And then, when it's applied to things like religion or philosophy, not just literature:

"It contends that a hermeneutic of doubt reduces religious experiences (and the believers committed to them) to something distant and 'other,' while a hermeneutic of trust enables scholars to reconstruct religious worldviews."

It vaguely echoes Rafal versus Pen. Or rather, Rafal's literary 'man versus society,' 'man versus self,' and 'man versus fate' conflicts.

"Sometimes a hermeneutic of suspicion may be important for more negative reasons, as when we suspect that texts are not telling us the whole truth."

This negative side to the concept can also somehow extend to fit typically skeptical Evil Rafal and repressed "Good" Rafal. (Sorry. After all this time, I refuse to call him strictly Good because his actions negate his soul's supposed Good status. I would love it if both brothers could each just consciously acknowledge their own capacity for Evil. Messy greyness like that would've been nice to see. But no! Rafal is/has to be "Good." [sigh.])

It's as if all this applied skepticism, this belief that there is something beneath the surface even when something/someone presents itself as trustworthy, (and probably, to some degree, it's also projecting your own untrustworthiness onto others as potential "traitors") is simply characteristic of Rafal. By my subjective interpretation, he probably mentally says: what reason have you given me to trust you? Or, vice versa: what reason have I given you to trust me? Or, at least, I tend to view him as paranoid, which could very well be exaggerating canon.

"The expression 'hermeneutic of suspicion' is a tautological way of saying what thoughtful people have always known, that words may not always mean what they seem to mean. Some forms of expression, such as allegory and irony, depend on this fact."

I do wonder if it's only because of sequential order that Rhian and Japeth feel more, idk, allegorical or "representational" (aside from just the Lion and the Snake roles, Japeth's mimicry of the first fratricide, and so forth) than Rhian and Rafal do? I think, partly, it could be because we get less page time of them overall, and partly because they're not quite "whole" entities, as in, the tale still technically belongs to Tedros and company. And the narrative doesn't always pin its focus on them.

And then, there's the argument against this school of thought:

"In sum, it is sometimes useful to 'see through' things, and suspicion has its place. If we insist, however, on 'seeing through' everything, we end up seeing nothing."

Ergo, Rafal's lack of self-awareness (and moments of misusing trust, like how he never reveals himself as the perceived threat of Fala) are probably part of his very own version of "seeing nothing" as he actively searches for "something" to find fault with (usually Rhian, let's face it) or it could be a case of seeing nothing wrong with his actions.

He starts to distance himself from Evil and turn to Good, doing too little, too late, while also being blind to Rhian's earlier losses and point of view. He thinks he himself is entirely deserving of what's coming to him, and at his most extreme, he's blind or rather, is caught in a sort of one-track mind, self-contained feedback loop? As if he has tunnel vision but in an upwards-ambition direction, that he reinforces with the total excess of pride embedded in the self-image he started out with.

And, this state of mind comes over him every single time he's sought out power above all and/or control over his immediate surroundings, without fail.

⸻

I had a Rhian and Rafal thought since I thought of a way to elaborate on something old. (Not sure if this one can apply to the second set of twins because I've no examples for it currently, but if you've got any thoughts, go right ahead!)

Originally, I assigned Rhian death of the author due to how he interferes with or foils the Storian's will (as the "author") in Fall by murdering Rafal so abruptly. Because, Rhian, especially in TLEA, in trying to rewrite the past and reshape the world, decides to interpret the texts of his world apart from the "author's" intention, imposing his own interpretations onto the texts (tales).

For comparison, return of the author or authorial intent could be seen as Rafal ceding to the Storian in the end, or considering the author as inseparable from his work, and seeing works in the original contexts they once inhabited, as products of their time.

Plus, Rafal would've been the Storian's intent, the One. And, the Storian had been drawing him, not Rhian, initially—well, assuming it had decided on Rafal and wasn't in on the twist, until the eye color change in the illustration, which seemingly could've signaled it knew the One was Rhian all along. Depends on how we interpret the scene, I suppose.

Or, perhaps, less sinisterly than the Pen just knowing and being complicit in the twist Rhian chose for the tale in taking Rafal's face and identity, the Pen could have conceded to Rhian's "interpretation," as a sort of "reader" of its tales over itself as the prime "author." Because, well, Rhian is called the "author of his own misfortune" by the narrative. Maybe, the Pen was handing over the authorship to him, in complying with what Rhian wanted, in that moment, so Rhian could bend the story to his own designs and ends.

⸻

I could see chivalry theory happening in the Endless Woods—that's an interesting one! Though, does Evelyn actually get a lenient sentence? She does die, and the "no longer useful" judgment Rafal barely passes over her is harsh.

Enjambment and caesura fit TCY twins well. If the plot and his plan didn't force him to be conscious of what he said, could Rhian have been as sociable as Sophie was? Do we ever see a side of him like that, like in the Beauty and the Feast chapter of QFG, for instance?

Ooh, the self-fulfilling prophecy and Becker's labeling theory remind me of the Pygmalion Effect (expectations shape behavior and self-image/people return what you invest in them) in psychology. I wonder if they're, by any chance, directly related, with one on a larger societal scale and the other on a smaller individual scale? Though, the Pygmalion Effect is more psychology than sociology, so maybe it wouldn't apply on a wider level? I don't know much at all about sociology, so thank you for the terms though!

The labeling happens to remind me of the concept of our subconscious "thin-slicing" stimuli, when we intuitively parse out new situations in split-second, snap judgments, with how the phenomenon is explained in a book, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell. It's not a terminology heavy book though, so maybe some things described in it were more colloquial than truly sociological.

Also, I love the term folk devil! It fits so well and it's in line with the Gavaldon assumptions! In fact, it fits Rafal even better than "scapegoat" ever could, or general moral panics/witch hunts/persecution, so thank you!!! I didn't really call him a "scapegoat" before because it sounded too "innocent" for him, and to be fair, in his case, he is more guilty/disruptive, and wasn't persecuted without reason, honestly. And, he can, unlike other actual victims, be compared to a literal demon beyond just how he's viewed.

Also, I think Japeth at certain points deserves to go into that same media circus kind of category too, considering how Rhian's plan initially forced him to take the blame for all the terrorism publicly as the Snake.

⸻

Ooh, you're absolutely right about the edgework angle being a part of the series, I'd say, and I think I might know how to fit it in!

It could apply to nontraditional villainy, to those who deliberately seek out a type of personal, "selfish" freedom from societal/structural constraints, like the Never kingdom of Akgul's entire philosophy to live by does, iirc, with its endless hedonism.

Of course, this kind of villainy would be the kind that Rafal sometimes appreciates and sometimes looks down on. For instance, he doesn't see as much Evil value/potential in the communal piracy or more social tendencies of the pirates, unlike true villains who work alone, while, at the same time, he does see the point to the revelry at The Black Rabbit—that's the thrill-seeking side of "Evil." (It's also a bit present in the 'No Ball.')

And, the Nevers in the main series are sort of known for their intrepidness, their recklessness, their raucousness. It's actually just their general "culture" of not allowing for cowardice, to the extreme, even at the expense of personal safety, all for the sake of reputation, even when "cowardice" is the smarter option. So, naturally, they have got a lot of grandstanding and brashness. They're all about putting on bravado! (And they also seem to be a dark mirror of the Everboys, in my opinion. They just take things further. Though, I guess they owe it to Rafal's deprivation early on, which must've reinforced the idea that they could do without a lot of the time because they're better than the "namby-pamby" Evers could ever be.)

Lastly, the best in-narrative example I think we have of this type of behavior is probably the cost of entry to The Black Rabbit: reporting sins, and how that practice is likely perpetuated by the very drinks they serve there, so the attendees can party all night long and do Storian knows what that's probably worse!

The Snake Venom drinks contain literal, real-world psychoactive ingredients (i.e., kola nuts and nutmeg/mace(?)). And these hallucinogens really do alter a person's state of mind. So, it's no wonder the Nevers are collectively predisposed to doing crime—just look at what they're being glutted with at mass public events! It's all built into a societal level other than soul.

⸻

By the way, if anyone had wanted to know about the updates to this post above and in all the reblogs, I'll tag everyone who seems to have shown interest:

@ciieli @horizonsandbeginnings @books-and-tears @loverofbooksandhistory @joeykeehl256

@heya-there-friends @2xraequalstorara @arcanaisarcana

@wisteriaum

SGE Characters as Literary Things

(Not all of these are actual literary or rhetorical devices; some are just writing techniques, forms, genres, mediums, etc.)

This is a bit abstract, so I’m curious about how subjective these might be. Does anyone agree or disagree? And feel free to make additions if you think I left anything out, or request another character that isn’t here.

Hopefully this makes (intuitive?) sense. As always, I'm willing to explain my thought process behind any of the things I've listed.

Also, anyone can treat this like a “Tag Yourself” meme, if you want. Whose list do you most relate to, use, or encounter?

⸻

LANCELOT (I know—how odd that I’m starting with a minor character and not Rafal, but wait. There’s a method to my madness. Also, watch out for overlap!):

Metonymy, synecdoche (no, literally, to me, these are him.)

Zeugma

Analogy

Figures of speech

Slang, argot

Colloquialisms

Idioms

TEDROS:

Simile

Metaphor

Rhyming couplets

Rhyme schemes

Sonnets

Commercial fiction

Coming-of-age genre

Line enjambment

Overuse of commas

Cadence, prose speech

Waxing poetic, verse (not prose)

Alliteration

Kinesthetic imagery

Phallic imagery/sword sexual innuendos (sorry)

The chivalric romance genre

AGATHA:

Anaphora, repetition

Semicolon, periods

Line breaks

Terse, dry prose

Semantics (not syntax)

Elegy

Resonance

Consonance, alliteration

Pseudonym

Narrative parallels

Realism

Satire

SOPHIE:

Sophistry (yes, there is a word for it!)

Imagery

Italics, emphasis

Em dash

Aphrodisiac imagery

Unreliable narrator, bias

Rashomon effect

Syntax (not semantics)

Diction

Chiasmus (think: “Fair is foul and foul is fair.”)

Rhetorical purpose

Provocation, calls to action

Voice, writing style

Rhetorical modes: pathos, logos, ethos

Metaphor

Hyperbole, exaggeration

Sensationalism, journalism

Surrealism

Verisimilitude

Egocentrism

Callbacks (but not foreshadowing or call-forwards)

Narrative parallels

Paralepsis, occultatio, apophasis, denial

Hypothetical dialogue

Monologue

JAPETH:

Sibilance

Lacuna

Villanelle (an obsessive, repetitive form of poetry)

Soliloquy

ARIC:

Sentence fragments

RHIAN (TCY):

Unreliable narrator

Setup, payoff

Chekhov’s gun

Epistolary novel

RHIAN (prequels):

Multiple povs

Perspective

Dramatic irony

Situational irony

Chiaroscuro (in imagery)

Endpapers

Frontispiece

Deckled edges

Narrative parallels

Foreshadowing

Call-forwards

Foil

Death of the author

RAFAL:

Omniscient narrator

Perspective

Surrealism

Etymology

Word families or 'linguistic ecosystems'

Latin

Verbal irony

Gallows humor

Narrative parallels

Call-forwards

Circular endings

Parallel sentences or balanced sentence structure

Narrative parallels

Foil

Juxtaposition

Authorial intent (“return of the author”)

HESTER:

Protagonist

Allusions

Gothic imagery

ANADIL:

Defamiliarization

Deuteragonist (second most important character in relation to the protagonist)

Psychic distance

Sterile prose

Forewords, prologues

Works cited pages

DOT:

Tone

Gustatory imagery

Tritagonist (third most important character in relation to the protagonist)

KIKO:

Sidekick

Falling action

Dedications, author's notes, epigraph, acknowledgements

Epitaph (Tristan)

BEATRIX:

Pacing

Rising Action

Climax

HORT:

Unrequited love

Falling resolution

Anticlimax

Malapropism

Innuendo

Asides

Brackets, parentheses

Cliché

EVELYN SADER:

Synesthetic imagery

Villanelle

Foreshadowing

AUGUST SADER:

Stream of consciousness style

Imagery

Foreshadowing

Coming-of-age genre

Elegy

Omniscience

Rhetorical questions

Time skips, non-linear narratives

Epilogues

MARIALENA:

Diabolus ex machina

Malapropism

Malaphors, mixed metaphors

Slant rhyme

Caveat

Parentheses

Footnotes

MERLIN:

Deus ex machina

Iambic pentameter

Filler words

BETTINA:

Screenwriting

Shock value

22 Essential Literary Devices and How to Use Them In Your Writing

hello, happy Monday. Hope you’re all having a wonderful day!

I will skip the pre-info and dive right into it.

What Is a Literary Device?

is a tool used by writers to hint at larger themes, ideas, and meaning in a story or piece of writing

The List of Literary Devices:

Allegory. Allegory is a literary device used to express large, complex ideas in an approachable manner. Allegory allows writers to create some distance between themselves and the issues they are discussing, especially when those issues are strong critiques of political or societal realities.

Allusion. An allusion is a popular literary device used to develop characters, frame storylines, and help create associations to well-known works. Allusions can reference anything from Victorian fairy tales and popular culture to the Bible and the Bard. Take the popular expression “Bah humbug”—an allusion that references Charles Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol. The phrase, which is often used to express dissatisfaction, is associated with the tale’s curmudgeonly character, Ebenezer Scrooge.

Anachronism. Imagine reading a story about a caveman who microwaves his dinner, or watching a film adaptation of a Jane Austen novel in which the characters text each other instead of writing letters. These circumstances are examples of anachronisms, or an error in chronology—the kind that makes audiences raise their eyebrows or do a double-take. Sometimes anachronisms are true blunders; other times, they’re used intentionally to add humor or to comment on a specific time period in history.

Cliffhanger. It’s a familiar feeling: You’re on minute 59 of an hour-long television episode, and the protagonist is about to face the villain—and then episode cuts to black. Known as a cliffhanger, this plot device marks the end of a section of a narrative with the express purpose of keeping audiences engaged in the story.

Dramatic Irony. Remember the first time you read or watched Romeo and Juliet? The tragic ending of this iconic story exemplifies dramatic irony: The audience knows that the lovers are each alive, but neither of the lovers knows that the other is still alive. Each drinks their poison without knowing what the audience knows. Dramatic irony is used to great effect in literature, film, and television.

Extended Metaphor. Extended metaphors build evocative images into a piece of writing and make prose more emotionally resonant. Examples of extended metaphor can be found across all forms of poetry and prose. Learning to use extended metaphors in your own work will help you engage your readers and improve your writing.

Foreshadowing. At its core, storytelling has one ambition: to capture and sustain your reader’s attention and keep them reading your story. Foreshadowing, or slyly indicating a future event, is one technique a writer can use to create and build suspense.

Humor. Humor brings people together and has the power to transform how we think about the world. Of course, not everyone is adept at being funny—particularly in their writing. Making people laugh takes some skill and finesse, and, because so much relies on instinct, is harder to teach than other techniques. However, all writers can benefit from learning more about how humor functions in writing.

Imagery. If you’ve practiced or studied creative writing, chances are you’ve encountered the expression “paint a picture with words.” In poetry and literature, this is known as imagery: the use of figurative language to evoke a sensory experience in the reader. When a poet uses descriptive language well, they play to the reader’s senses, providing them with sights, tastes, smells, sounds, internal and external feelings, and even deep emotion. The sensory details in imagery bring works to life.

Irony. Irony is an oft-misunderstood literary device that hinges on opposites: what things are on the surface, and what they end up actually being. Many learn about dramatic irony through works of theater like Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet or Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex. When deployed with skill, irony is a powerful tool that adds depth and substance to a piece of writing.

Metaphor, Simile, and Analogy. Metaphors, similes, and analogies are three techniques used in speech and writing to make comparisons. Each is used in a different way, and differentiating between the three can get a little tricky: For example, a simile is actually a subcategory of metaphor, which means all similes are metaphors, but not all metaphors are similes. Knowing the similarities and differences between metaphor, simile, and analogy can help you identify which is best to use in any scenario and help make your writing stronger.

Motif. A motif is a repeated element that has symbolic significance to a story. Sometimes a motif is a recurring image. Sometimes it’s a repeated word or phrase or topic. A motif can be a recurrent situation or action. It can be a sound or a smell or a temperature or a color. The defining aspect is that a motif repeats, and through this repetition, a motif helps to illuminate the central ideas, themes, and deeper meaning of the story in which it appears.

Motif vs. Symbol. Both motifs and symbols are used across artistic mediums: Painters, sculptors, playwrights, and musicians all use motifs and symbols in their respective art forms. And while they are similar literary terms, “motif” and “symbol” are not synonyms.

Oxymoron. An oxymoron is a figure of speech: a creative approach to language that plays with meaning and the use of words in a non-literal sense. This literary device combines words with contradictory definitions to coin a new word or phrase (think of the idiom “act naturally”—how can you be your natural self if you’re acting?). The incongruity of the resulting statement allows writers to play with language and meaning.

Paradox. “This sentence is a lie.” This self-referential statement is an example of a paradox—a contradiction that questions logic. In literature, paradoxes can elicit humor, illustrate themes, and provoke readers to think critically.

Personification. In writing, figurative language—using words to convey a different meaning outside the literal one—helps writers express themselves in more creative ways. One popular type of figurative language is personification: assigning human attributes to a non-human entity or inanimate object in an effort to express a point or idea in a more colorful, imaginative way.

Satire. Satire is so prevalent in pop culture that most of us are already very familiar with it, even if we don’t always realize it. Satire is an often-humorous way of poking fun at the powers that be. Sometimes, it is created with the goal to drive social change. Satire can be part of any work of culture, art, or entertainment—it has a long history, and it is as relevant today as it was in ancient Rome.

Situational Irony. Irony: it’s clear as mud. Theorists quibble about the margins of what constitutes irony, but situational irony is all around us—from humorous news headlines to the shock twists in a book or TV show. This type of irony is all about the gap between our expectations and reality, and it can make a memorable and powerful impression when we encounter it.

Suspense. No matter what type of story you’re telling, suspense is a valuable tool for keeping a reader’s attention and interest. Building suspense involves withholding information and raising key questions that pique readers’ curiosity. Character development plays a big role in generating suspense; for example, if a character’s desire is not fulfilled by the end of the book, the story will not feel complete for the reader.

Symbolism. An object, concept, or word does not have to be limited to a single meaning. When you see red roses growing in a garden, what comes to mind? Perhaps you think literally about the rose—about its petals, stem, and thorns, or even about its stamen and pistil as a botanist might. But perhaps your mind goes elsewhere and starts thinking about topics like romance, courtship, and Valentine’s Day. Why would you do this? The reason, of course, is that over the course of many generations, a rose’s symbolic meaning has evolved to include amorous concepts.

Verisimilitude. Verisimilitude (pronounced ve-ri-si-mi-li-tude) is a theoretical concept that determines the semblance of truth in an assertion or hypothesis. It is also an essential tenet of fiction writing. Verisimilitude helps to encourage a reader’s willing suspension of disbelief. When using verisimilitude in writing, the goal is to be credible and convincing.

Vignette. A writer’s job is to engage readers through words. Vignettes—poetic slices-of-life—are a literary device that brings us deeper into a story. Vignettes step away from the action momentarily to zoom in for a closer examination of a particular character, concept, or place. Writers use vignettes to shed light on something that wouldn’t be visible in the story’s main plot.

I’ll make a post going into each of them individually in more detail later on!

Like, reblog and comment if you find this useful! If you share on Instagram tag me perpetualstories

Follow me on tumblr and Instagram for more writing and grammar tips and more!

• An Oxford comma walks into a bar, where it spends the evening watching the television, getting drunk, and smoking cigars.

• A dangling participle walks into a bar. Enjoying a cocktail and chatting with the bartender, the evening passes pleasantly.

• A bar was walked into by the passive voice.

• An oxymoron walked into a bar, and the silence was deafening.

• Two quotation marks walk into a “bar.”

• A malapropism walks into a bar, looking for all intensive purposes like a wolf in cheap clothing, muttering epitaphs and casting dispersions on his magnificent other, who takes him for granite.

• Hyperbole totally rips into this insane bar and absolutely destroys everything.

• A question mark walks into a bar?

• A non sequitur walks into a bar. In a strong wind, even turkeys can fly.

• Papyrus and Comic Sans walk into a bar. The bartender says, "Get out -- we don't serve your type."

• A mixed metaphor walks into a bar, seeing the handwriting on the wall but hoping to nip it in the bud.

• A comma splice walks into a bar, it has a drink and then leaves.

• Three intransitive verbs walk into a bar. They sit. They converse. They depart.

• A synonym strolls into a tavern.

• At the end of the day, a cliché walks into a bar -- fresh as a daisy, cute as a button, and sharp as a tack.

• A run-on sentence walks into a bar it starts flirting. With a cute little sentence fragment.

• Falling slowly, softly falling, the chiasmus collapses to the bar floor.

• A figure of speech literally walks into a bar and ends up getting figuratively hammered.

• An allusion walks into a bar, despite the fact that alcohol is its Achilles heel.

• The subjunctive would have walked into a bar, had it only known.

• A misplaced modifier walks into a bar owned by a man with a glass eye named Ralph.

• The past, present, and future walked into a bar. It was tense.

• A dyslexic walks into a bra.

• A verb walks into a bar, sees a beautiful noun, and suggests they conjugate. The noun declines.

• A simile walks into a bar, as parched as a desert.

• A gerund and an infinitive walk into a bar, drinking to forget.

• A hyphenated word and a non-hyphenated word walk into a bar and the bartender nearly chokes on the irony

- Jill Thomas Doyle

Thanks for the tag @madi-konrad! This was quite an easy one. Anyone who’s read even a little bit of my writing will know that I love using out-of-pocket similes. The more ridiculous, the better. Things like:

I look at him like he has a dick glued to his forehead.

Everyone’s looking at me like I’ve farted in church.

(Those are actual similes you can find in The Tengu And The Angel BTW.)

Mythological imagery is also something I’m big on. I seem to have a thing for angels in particular, as I keep giving angelic names to my characters (Nathaniel, Azrael, Raphael, Ariel and Raziel, to name just a few.). I would like to use more tengu imagery in my writing, as I’m completely fascinated by tengu, but so far Kunio is the only character I’ve been able to apply it to. Maybe in future I’ll write characters who are actual tengu…

Oh, and metaphors too. Mythological metaphors, and out-of-pocket metaphors. I like to use a healthy blend of both.

Tagging @corvys-clover and @pcm-vandermeer!

writers reblog with your three favourite literary devices mine are repetition alliteration and metaphor

8 Theses or Disputations on Modern Christianity’s View of the Bible

By Author Eli Kittim

——-

A Call For a *New Reformation*

A common bias of modern Christianity is expressed in this way:

“If your doctrine damages other Biblical

doctrines, you’ve gotta change your

doctrine” (see “Galatians 5:1-12 sermon by

Dr. Bob Utley”; YouTube video).

Not necessarily. Maybe the previous Biblical doctrines need to change in light of new discoveries. Bible scholarship is still evolving like every other discipline. No one can say to Einstein: “if your theory damages previous theories, you’ve gotta change your theory.” What if the previous theories are wrong? Are we to view them as infallible?

What did the Reformers mean by sola scriptura? They meant that the Bible alone provides the “constitutive tenets of the Christian faith.” In other words, the basic tenets of the faith (e.g. credal formulations) are NOT to be found in papal decrees or councils but in the Bible alone! And they went to great lengths to show how both the church and its councils had made many mistakes.

If I can similarly demonstrate that the constitutive tenets of the Christian faith are wrong, and that the Bible contradicts modern Christianity, as the reformers did, then I, too, must call for a *new reformation*! Those hard core adherents of historical Christianity will of course excoriate me as a peddler of godless heresies without honestly investigating my multiple lines of evidence.

——-

1. The New Testament is an Ancient Eastern Text Employing the Literary Conventions of its Time

The New Testament doesn’t use 21st century propositional language but rather Eastern hyperbolic language, parables, poetry, paradox, and the like. Today, any story about a person is immediately seen as a biography. But in those days it could have been a poetic literary expression, akin to what we today would call, “theology.” The gospel writers adopted many of the literary conventions of the ancient writings and created what would be analogous to Greek productions (see Dennis MacDonald’s seminal work, “The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark”). We often miss the genre of the gospels by looking at it with modern western lenses.

——-

2. The Gospel Genre Is Not Biographical

This is the starting point of all the hermeneutical confusion. The gospels are not biographies or historiographical accounts. As most Bible scholars acknowledge, they are largely embellished theological documents that demonstrate the presence of “intertextuality” (i.e. a heavy literary dependence on the Old Testament [OT]). If we don’t understand a particular genre out of which a unique discourse is operating from, then we will inevitably misinterpret the text. So, the assumption that the gospels are furnishing us with biographical information seems to be a misreading of the genre, which appears to be theological or apocalyptic in nature. It is precisely this quasi-biographical literary form that gives the “novel” some verisimilitude. How can we be sure? Let’s look at the New Testament (NT) letters. The epistles apparently contradict the gospels regarding the timeline of Christ’s birth, death, and resurrection by placing it in eschatological categories. The epistolary authors deviate from the gospel writers in their understanding of the overall importance of eschatology in the chronology of Jesus. For them, Scripture comprises revelations and “prophetic writings” (see Rom. 16.25-26; 2 Pet. 1.19-21; Rev. 22.18-19)! According to the NT Epistles, the Christ will die “once for all” (Gk. ἅπαξ hapax) “at the end of the age” (Heb. 9.26b), a phrase which consistently refers to the end of the world (cf. Mt. 13.39-40, 49; 24.3; 28.20). Similarly, just as Heb. 1.2 says that the physical Son speaks to humanity in the “last days,” 1 Pet. 1.20 (NJB) demonstrates the eschatological timing of Christ’s *initial* appearance with unsurpassed lucidity:

“He was marked out before the world was

made, and was revealed at the final point of

time.”

——-

3. NT Scholars Demonstrate that the Gospels Are Not Historical

During his in-depth dialogue with Mike Licona on the historical reliability of the NT (2016), Bart Ehrman stated that “the NT gospels are historically unreliable accounts of Jesus.” In his book, “The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach,” NT scholar Michael Licona has actually de-historicized parts of the gospel (i.e. Mt. 27.51-53), showing, for example, that the resurrection of the saints after Jesus’ crucifixion is indicative of a non-literal, apocalyptic genre rather than of an actual historical event. Licona suggests that the appearance of angels at Jesus’ tomb after the resurrection is legendary. He considers parts of the gospels to be “poetic language or legend,” especially in regard to the raising of some dead saints at Jesus’ death (Mt. 27.51-54) and the angel(s) at the tomb (Mk 15.5-7; Mt. 28.2-7; Lk 24.4-7; Jn 20.11-13). NT scholar, James Crossley agrees that the purported events of Mt. 27.52-53 didn’t happen. Licona is, in some sense, de-mythologizing the Bible in the tradition of Rudolf Bultmann. This infiltration of legend in Matthew extends to all the other gospels as well. According to the book called “The Jesus Crisis” by Robert L. Thomas and F. David Farnell, two NT scholars, the sermon on the mount didn’t happen. The commissioning of the 12 did not happen. The parables of Matthew 13 and 14 didn’t happen. According to this book, it’s all made up. The magi? Fiction. The genealogy? Fiction! Robert H. Gundry, a professor of NT studies and koine Greek, has also said that Matthew 1-3 (the infancy narratives) were historical fiction (Midrash). Similarly, NT scholar Robert M. Price argues that all the Gospel stories of Jesus are a kind of midrash on the OT, and therefore completely fictional. Thomas L. Brodie, a Dominican priest, author, and academic, has similarly emphasised that most of the gospel thematic material is borrowed from the Hebrew Bible. These scholarly views have profound implications for so-called “historical Christianity,” its systematic theology, and its doctrines. Moreover, British NT scholar, James Dunn thought that the resurrection of Christ didn’t happen. He thought that Jesus was not resurrected in Antiquity but that Jesus probably meant he would be resurrected at the last judgment! What is more, Ludermann, Crossan, Ehrman, Bultmann all think that the resurrection is based on visions. So does Luke! No one saw Jesus during or after the so-called resurrection. The women saw a “vision” (Lk 24.23–24) just as the eyewitnesses did who were said to be “chosen beforehand” in Acts 10.40–41. Similarly, Paul only knows of the divine Christ (Gal. 1.11–12). With regard to the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus, where more than 500 people supposedly saw Christ, Paul suggests that they all saw him just as he did. He declares: “Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared ALSO to me” (1 Cor. 15.8 emphasis added). In other words, in saying “also to me; Gk. κἀμοί), Paul suggests that Christ appeared to others in the same way or manner that he appeared to him (that is to say, by way of “visions”)!

——-

4. A Few Examples of Legendary Elements in the Gospels

A few examples from the gospels serve to illustrate these points. From the point of view of form criticism, it is well-known among biblical scholars that The Feeding of the 5,000 (aka the "miracle of the five loaves and two fish") in Jn 6.5-13 is a literary pattern that can be traced back to the OT tradition of 2 Kings 4.40-44. Besides the parallel thematic motifs, there are also near verbal agreements: "They shall eat and have some left” (2 Kings 4.43). Compare Jn 6.13: “So they gathered ... twelve baskets ... left over by those who had eaten.” The magi are also taken from Ps. 72.11: “May all kings fall down before him.” The phrase “they have pierced my hands and my feet” is from Ps. 22.16; “They put gall in my food and gave me vinegar for my thirst” is from Psalm 69.21. The virgin birth comes from a Septuagint translation of Isaiah 7.14. The “Calming the storm” episode is taken from Ps. 107.23-30, and so on & so forth. Is there anything real that actually happened which is not taken from the Jewish Bible? Another example demonstrates the legendary nature of the Trial of Jesus. Everything about the trial of Jesus is at odds with what we know about Jewish Law and Jewish proceedings.

Six trials occur between Jesus’ arrest and crucifixion:

Jewish Trials

1. Before Annas

2. Before Caiaphas

3. Before the Sanhedrin

Roman Trials

4. Before Pilate

5. Before Herod

6. Before Pilate

Every single detail of each and every trial is not only illegal, but utterly ridiculous to be considered as a historical “fact.”

Illegalities ...

a) Binding a prisoner before he was condemned was illegal.

b) It was also illegal for Judges to participate in the arrest of the accused.

c) It was also illegal to have legal proceedings, legal transactions, or conduct a trial at night. It’s preposterous to have a trial going on in the middle of the night.

d) According to the law, although an acquittal may be pronounced on the same day, any other verdict required a majority of two and must come on a subsequent day. This law was also violated.

e) Moreover, no prisoner could be convicted on his own evidence. However, following Jesus’ reply under oath, a guilty verdict was pronounced!

f) Furthermore, it was the duty of a judge to make sure that the interest of the accused was fully protected.

g) The use of violence during the trial was completely unopposed by the judges (e.g. they slapped Jesus around). That was not just illegal; that kind of thing just didn’t happen.

h) The judges supposedly sought false witnesses against Jesus. Also illegal.

i) In a Jewish court room the accused was to be assumed innocent until proved guilty by two or more witnesses. This was certainly violated here as well.

j) No witness was ever called by the defense (except Jesus’ self incrimination testimony). Not just illegal; unheard of.

k) The Court lacked the civil authority to condemn a man to death.

l) It was also illegal to conduct a session of the court on a feast day (it was Passover).

m) Finally, the sentence is passed in the palace of the high priest, but Jewish law demanded that it be pronounced in the temple, in the hall of hewn stone. They didn’t do that either.

n) Also, the high priest is said to rend his garment (that was against the law). He was never permitted to tear his official robe (Lev. 21:10). For example, without his priestly robe he couldn’t have put Christ under oath in the first place.

Thus, all these illegalities according to Jewish law are not only quite unimaginable but utterly unrealistic to have happened in history.

——-

5. Bart Ehrman Says That Paul Tells Us Nothing About the Historical Jesus

One of the staunch proponents of the historical Jesus position is the renowned textual scholar Bart Ehrman, who, surprisingly, said this on his blog:

“Paul says almost *NOTHING* about the

events of Jesus’ lifetime. That seems weird

to people, but just read all of his letters.

Paul never mentions Jesus healing anyone,

casting out a demon, doing any other

miracle, arguing with Pharisees or other

leaders, teaching the multitudes, even

speaking a parable, being baptized, being

transfigured, going to Jerusalem, being

arrested, put on trial, found guilty of

blasphemy, appearing before Pontius Pilate

on charges of calling himself the King of the

Jews, being flogged, etc. etc. etc. It’s a

very, very long list of what he doesn’t tell us

about.”

——-

6. The External Evidence Does Not Support the Historicity of Jesus

A) There are no eyewitnesses.

B) The gospel writers are not eyewitnesses.

C) The epistolary authors are not eyewitnesses.

D) Paul hasn’t seen Jesus in the flesh.

E) As a matter of fact, no one has ever seen or heard Jesus (there are no firsthand accounts)!

F) Contemporaries of Jesus seemingly didn’t see him either; otherwise they’d have written at least a single word about him. For example, Philo of Alexandria is unaware of Jesus’ existence.

G) Later generations didn’t see him either because not even a passing reference to Jesus is ever written by a secular author in the span of approximately 65y.

H) The very first mention of Jesus by a secular source comes at the close of the first century (93-94 CE). Here’s the scholarly verdict on Josephus’ text: “Almost all modern scholars reject the authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum in its present form” - wiki

I) Even Kurt Åland——the founder of the Institute for NT textual Research, who was also a textual critic and one of the principal editors of the modern critical NT——questioned whether Jesus existed! In his own words: “it almost then appears as if Jesus were a mere PHANTOM . . . “ (emphasis added)! Bertrand Russell, a British polymath, didn’t think Christ existed either. He said: “Historically it is quite doubtful whether Christ ever existed at all” (“Why I am not a Christian”).

J) Interestingly enough, even though scholars usually reject the historicity of Noah, Abraham, and Moses, they nevertheless support the historicity of Jesus, which seems to be a case of special pleading. In his article, “Beware of Consensus Theology,” Dr. Stephen R. Lewis correctly writes:

there have been so many things society has held

as true when in fact they are merely a consensus.

. . . We must beware of our own “consensus

theology.” . . . We must beware of allowing the

theology of anyone—Augustine, Martin Luther,

John Calvin, or whomever—to take precedence

over the teachings of Scripture.

——-

7. First Peter 1.10-11 Suggests An Eschatological Soteriology:

“Concerning this salvation, the prophets, who spoke of the grace that was to come to you, searched intently and with the greatest care, trying to find out the time and circumstances to which the Spirit of Christ in them was pointing when he predicted the sufferings of the Messiah and the glories that would follow” (1 Pet. 1.10-11 NIV).

Exegesis

First, notice that the prophets (Gk. προφῆται) in the aforementioned passage are said to have the Spirit of Christ (Gk. Πνεῦμα Χριστοῦ) within them, thereby making it abundantly clear that they are prophets of the NT, since there’s no reference to the Spirit of Christ in the OT. That they were NT prophets is subsequently attested by verse 12 with its reference to the gospel:

“It was revealed to them that they were not

serving themselves but you, when they

spoke of the things that have now been told

you by those who have preached the gospel

to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven.”

Second, the notion that 1 Peter 1.10-11 is referring to NT as opposed to OT prophets is further established by way of the doctrine of salvation (Gk. σωτηρίας), which is said to come through the means of grace! This explicit type of Soteriology (namely, through grace; Gk. χάριτος) cannot be found anywhere in the OT.

Third, and most importantly, observe that “the sufferings of the Messiah and the glories that would follow” were actually “PREDICTED” (Gk. προμαρτυρόμενον; i.e., testified beforehand) by “the Spirit of Christ” (Gk. Πνεῦμα Χριστοῦ; presumably a reference to the Holy Spirit) and communicated to the NT prophets so that they might record them for posterity’s sake (cf. v. 12). Therefore, the passion of Christ was seemingly written in advance—-or prophesied, if you will—-according to this apocalyptic NT passage!

_______________________________________

Here’s Further Evidence that the Gospel of Christ is Promised Beforehand in the NT. In the undermentioned passage, notice that it was “the gospel concerning his Son” “which he [God] promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy scriptures.” This passage further demonstrates that these are NT prophets, since there’s no reference to “the gospel (Gk. εὐαγγέλιον) of God … concerning his Son” in the OT:

“Paul, a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be

an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God,

which he promised beforehand through his

prophets in the holy scriptures, the gospel

concerning his Son” (Rom. 1.1-3 NRSV).

Moreover, Paul’s letters are referred to as “Scripture” in 2 Pet. 3.16, while Luke’s gospel is referred to as “Scripture” in 1 Tim. 5.18!

——-

8. Conclusion: NT History is Written in Advance

The all-pervading scriptural theme——that Christ’s gospel, crucifixion, and resurrection is either promised, known, or witnessed *beforehand* by the foreknowledge of God——should be the guiding principle for NT interpretation. First, we read that “the gospel concerning his [God’s] Son” is “promised beforehand (προεπηγγείλατο; Rom. 1.2). Second, the text reveals that Jesus was foreknown to be crucified “according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” (προγνώσει; Acts 2.22-23). Third, this theme is reiterated in Acts 10.40-41 in which we are told that Jesus’ resurrection is *only* visible “to witnesses who were chosen beforehand by God” (προκεχειροτονημένοις; NASB). Accordingly, the evidence suggests that the knowledge of Christ’s coming was communicated beforehand to the preselected witnesses through the agency of the Holy Spirit (cf. Jn 16.13; 2 Pet. 1.17-19 ff.). It appears, then, that the theological purpose of the gospels is to provide a fitting introduction to the messianic story beforehand so that it can be passed down from generation to generation until the time of its fulfilment. It is as though New Testament history is written in advance:

“I am God . . . declaring the end from the

beginning and from ancient times things

not yet done (Isa. 46.9-10).

Mine is the only view that appropriately combines the end-time messianic expectations of the Jews with Christian Scripture!

What if the Crucifixion of Christ is a future event? (See my article “WHY DOES THE NEW TESTAMENT REFER TO CHRIST’S FUTURE COMING AS A REVELATION?”: https://eli-kittim.tumblr.com/post/187927555567/why-does-the-new-testament-refer-to-christs).

——-

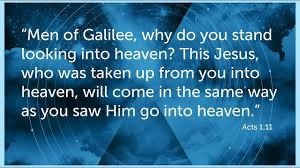

This Same Jesus Will Come in Like Manner

By Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

According to the literary story, after his purported ascension into heaven, two angels make their appearance and instruct humanity not to look to the sky but to the earth in order to find Jesus. In Acts 1:11 (NKJV), the angels proclaim:

Men of Galilee, why do you stand gazing up

into heaven? This same Jesus, who was

taken up from you into heaven, will so come

in like manner as you saw Him go into

heaven.

What did the multitudes see? First and foremost, they saw Jesus standing on the earth prior to his ascension. Therefore, the angels ask, “why do you stand gazing up into heaven?” That is to say, why do you anticipate Christ’s coming from the heavens? Contrary to all expectations, he “will so come in like manner as you saw Him go”; in other words, as a man!

The angels are there to disclose the prophecy of Christ’s future coming. That seems to be their primary concern. But if Christ will come in human form, then this eye-opening verse must be illustrating the prophecy that will occur at the end of time, namely, Jesus’ ascension into heaven (cf. Rev. 12.5)!

There are some misleading translations that are based on the translator’s *theological bias,* which are not faithful to the original Greek text. Some of these inaccurate translations are the NIV, NLT, BSB, CEV, GNT, ISV, AMP, GW, NET Bible, NHEB, & WEB. All these Bible versions mistranslate the verse as if Jesus “will come back” or “will return.” However, the original Greek uses a word that does not imply a “coming back” or a “return.” It simply indicates *one* single coming. The Greek text uses the word ἐλεύσεται, which simply means “will come”!

So, Acts 1.11 seems to be part of an apocalyptic literary genre of prophetical writing, which can be summed up in the following statement:

This same Jesus … will so come in like manner as you saw Him go …

The revelation comes by way of a logical equation. It goes something like this: a) if Jesus was seen in *human form* before he left, & b) if he will come in the exact same *form* as when he left, then it follows that c) Jesus will come in human form. The prophecy is that although most people expect him to come from the sky, the truth is, he will come from the earth!

Given that he doesn’t come to the earth repeatedly but rather “once for all” (Heb. 7.27; 9.26), and since Acts 1.11 indicates in what form he will appear, it means that Christ will come “once for all” as a man. In other words, the ascension story in the text must necessarily be a literary device through which to reveal the prophecy that was seen in a vision!

Question: In what manner did they see Jesus go?

Answer: In human form!

Question: In what manner is Jesus said to come?

Answer: In like manner: as a man!

——-

Here’s another Bible Version (Acts 1.11 NASB) which illustrates the exact same idea. Try meditating on this riddle:

This Jesus … will come in the same way as

you have watched Him go …

——-

odysseus absolutely does present a threat to penelope if he perceives her as at all unfaithful, and i feel the unfairness of this, and i think people tend to undersell how much tension at least potentially exists between odysseus and penelope. but i'm also like. his reaction, all speculation aside, his actual reaction in the odyssey to her flirting with the suitors is delight, because he immediately ascertains that she is running a con. sorry that they're so in-sync in spite of the forces that try to drive a wedge between them, including their own misgiving hearts. sorry that they invented homophrosyne ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Example of what you get when you open Chekhov’s Box:

imagination (1963) - harold ordway rugg

"chekhovs cat / schrödingers razor / occams gun"

thinking about how most idioms have been dissected and had sections removed so that they can fit the expectations of society and be used to reinforce the ideals that the original version were exactly opposed to and how their meanings have been defaced and distorted to mean what we want them to mean.

example: “blood runs thicker than water” is actually “the blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb”

or

“birds of a feather flock together” is actually “birds of a feather flock together until the cat comes”

OR

“an eye for an eye” is ACTUALLY “an eye for an eye, a teeth for a teeth, and soon everyone will be blind and toothless”

tldr: screw the status quo, learn the full, unedited version of idioms